On the surface, the way Holacracy deals with projections and deadlines may seem counter-intuitive, or at times, just crazy.

For example, if I look you in the face and promise you I’ll finish a particular project by Friday, you absolutely should NOT believe me. If your reaction is, “Huh?!” then you’re in the right place.

Projections are confusing because to really get them, you have to understand several paradigm shifts simultaneously. The good news is that if you can really understand how projections work, and more importantly, why they work, then you’ll understand a lot about Holacracy in general. That’s a tall order, which is why this article is longer than usual.

Note: I’ve got so much to say about projections, I’ve written three articles. Part 2 is titled, “Best Practices for Requesting & Giving Rough Estimates.” Part 3 explains why you should pay particular attention when someone says things like, “I don’t want to bother you,” or, “Keep me posted.”

Here’s a summary of what you need to know for now…

- A projection is only a rough estimate, never a binding commitment, promise, or agreement.

- Projections allow us to distinguish a commitment to a relationship from a commitment to achieve a specific outcome.

- Outcomes involve many components including importance and timeframe, but projections only deal with the timeframe.

- Projections help us avoid creating fake deadlines to get people to do things.

- Projections highlight that we don’t actually want time-management; we want attention-management.

- Projections allow us to keep the tensions with the roles that sense them.

- Projections allow us to redefine what it means to trust someone.

1. A Projection is only a rough estimate, never a binding commitment, promise, or agreement.

Let’s start with what the Holacracy constitution actually says about projections:

You must provide a projection of the date you expect to complete any Project or Next-Action tracked for any of your Roles in the Circle. A rough estimate is sufficient, considering your current context and priorities, but without detailed analysis or planning. This projection is not a binding commitment in any way, and unless Governance says otherwise, you have no duty to track the projection, manage your work to achieve it, or follow-up with the recipient if something changes. §Section 4.1.1(c).

Now, what does that mean? In essence, when it comes to the work of your roles, you’re not allowed to commit to someone else’s deadline. I’ll say that again. You cannot commit to someone else’s deadline. The rules don’t allow you to.

This doesn’t mean you should ignore deadlines in general. If you want to fly to Chicago on Tuesday, the plane isn’t going to wait for you. This just means you’re not allowed to commit to someone else’s deadline (see more about the use of fake deadlines in #4).

But notice that the rule ALSO says you must provide a projection when asked. You have to be transparent. So, if someone asks when you’ll be done with the report, even if you think they’re challenging your competence, you can’t just say, “Don’t worry…just trust me.” No. You must give them an estimate of when you think you’ll likely get it done.

And after you’ve given a projection, even if things change, you have no obligation to let anyone know. BUT…you’re required to provide updates every time you’re asked for one. So, if someone asks you for a projection on something every day for ten days, you must provide a projection every day.

This first point to get is that a projection, or “rough estimate,” is very different than a commitment, promise, or agreement (I’ll use those three words interchangeably).

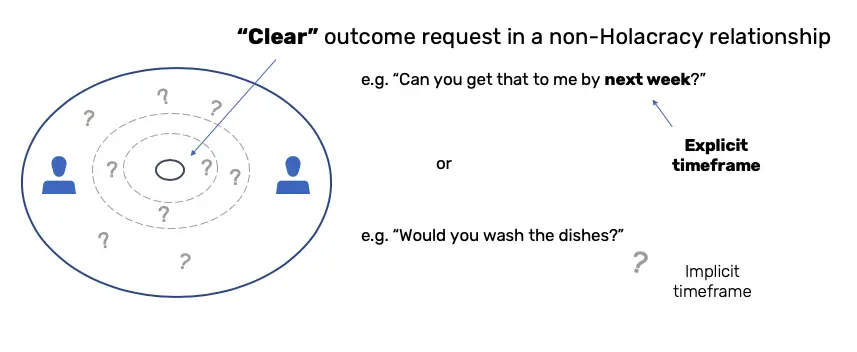

So, a good projection-request sounds like this: “Will you give me a projection on when you expect you’ll likely get the sales report completed?” Not, “Hey, can you get the sales report done by tomorrow?”

2. Projections allow us to distinguish a commitment to a relationship from a commitment to achieve a specific outcome.

“It’s an inappropriate use of love and care to USE love and care to effect a result.”

David Allen

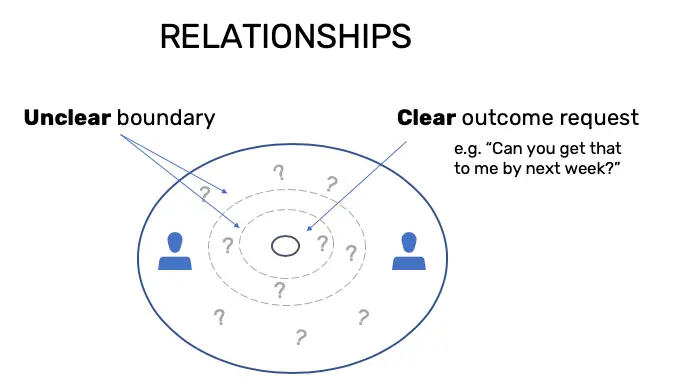

Normally, we can get someone to commit to an outcome that we care about because we have a relationship with that person. Since they care about us and we care about the specific outcome, it seems reasonable to expect that they should care about the outcome too. We don’t generally go around expecting strangers to do things for us.

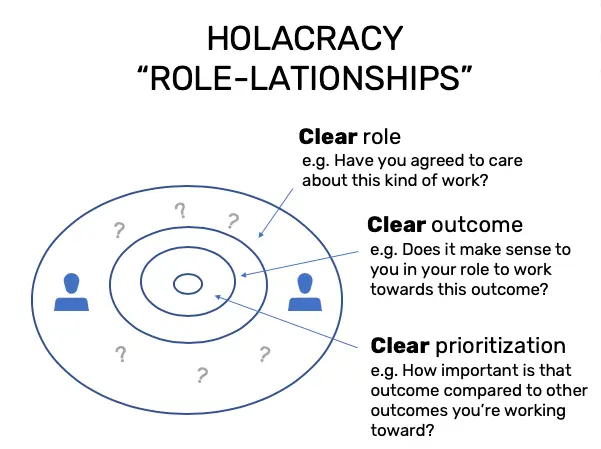

But Holacracy allows us to make finer distinctions within the relationship space, thus giving us several checkpoints which we don’t usually have. By knowing that each party has made conscious choices along the way about what makes sense for them to care about generally (i.e. energizing a role), and what outcomes make sense to work towards (i.e. projects that their role cares about), we eliminate the need to rely upon the get-their-commitment-approach as the only way to get confidence something is going to happen.

Note: The “Get-their-commitment approach” is identical to “What-by-When”, as outlined in Brian Robertson’s article, “The Insanity of What-by-When.”

Practicing Holacracy means we transform a single question like, “Will you agree to do this?” or, “Will you commit to doing this?” into several more specific questions that provide clarity on any agreements relevant to that outcome.

The first is, “Has this person agreed to take a role that considers this kind of work?” There’s no point in asking me to do something like update the website if I don’t have any roles that have anything to do with the website. But let’s say I actually do fill a role called, “Website Manager” which has an accountability for, “Updating the website,” which means that you’re at least speaking with the right person.

OK, but now the next question you’d ask me is, “Does it make sense to you in your role to work towards this specific outcome? Let’s say you want me to change the website font from Times New Roman to Arial.

At this point, you’re not asking me if I want to do it, or if I have time to do it. You just want to figure out if that outcome would make sense to work towards in that role. Meaning, we’re intentionally holding off on questions about time for the moment. So, the question at this point is really something like, “Does it make sense to work towards this…if you had no other competing priorities?” If so, I’ll immediately document it as a project and work on it whenever I can.

At this point, maybe that’s all you need to ask. You wanted a specific outcome, “website font updated,” and I’ve accepted the project, so you can move on with your day comfortable in the knowledge that I’m going to own and drive that project forward (Note: This is because I said it made sense to me to work toward; i.e. I didn’t accepted it because I was told to, or just because it made sense to someone else). And again, maybe that’s all you needed.

Or you might ask, “How important is that outcome compared to other outcomes you are working toward?” And if I tell you, “Yep, updating the website font is the most important thing I’m working on,” then maybe you’ll feel even more comfortable and confident about the whole thing.

And whew. That’s a lot of questions to ask. Wouldn’t it just be easier to say, “Hey, will you do this?” And the answer is, yes, it would. And it still will be when you’re using Holacracy’s rules. The point isn’t to force you into clarity.

They are simply options when you don’t have clarity on some aspect of the outcome– options that are needed because without these questions, as we are in most relationships, we can only lean on one of two levels of conscious commitment, either; 1) their commitment to do a very specific thing (e.g. “I need you to commit to this”); or 2) their commitment to the relationship itself (i.e. we need to do favors for each other otherwise we’ll damage our relationship) (for more on this, see #7).

3. Outcomes involve many aspects including importance and timeframe, but projections only deal with the timeframe.

“Ladies, if a man says he will fix something, he will fix it. You don’t have to remind him every six months.”

Unknown

Normally, commitments work because we have clarity. If you agree to “Bring me to the airport on Sunday,” maybe that’s good enough. Maybe it’s not. Maybe you need to know what time. Or which airport.

Going back to the “Website fonts updated” project, what if all the information you’ve gathered from the Holacracy-style questions still doesn’t help you; what if you need me to update the website today?

Ah! Well, then you need clarity over my expected timeframe, which of course is a request for a projection (e.g. “When do you think you’ll likely update the website?”). And it’s distinct from the question of importance (i.e. prioritization), but can easily, and confusingly, be conflated with the definition of the outcome itself.

That is, if you asked me to update the website, and I said, “Sure thing! It’ll be the first thing I do next year,” you probably wouldn’t consider that an agreement at all. For you, having an updated website a year from now won’t resolve your tension.

Sometimes it really helps to get clear on the estimated timeframe for an outcome, but that’s not always easy to do. We often don’t even notice that all outcomes include some element of time, which could be pulled out and evaluated separately.

The other major source of confusion is the issue of importance. This is a question of prioritization. And by default, every role filler is responsible for prioritizing their own work moment-to-moment in alignment with the constitution (which includes some standard prioritization like, “Processing inbounds over your own work”), and any official prioritizations you’ve been given by a relevant Lead Link.

But here’s the thing: strictly-speaking, a prioritization doesn’t say when something will get done. A prioritizations tell you which outcome is more important relative to the others, but that’s all it tells you. Other factors, like available time or energy, or the context you’re in, will also help determine what you may do at any moment.

Holacracy’s rules help us here by having separate rules for requesting that someone work towards a specific outcome (i.e. “project”), requiring someone to give you transparency into their prioritization, and requiring transparency into an estimated timeframe (i.e. “projection”). We can get as granular as we need to.

4. Projections help us avoid creating fake deadlines to get people to do things.

“Over the last two decades, one approach to overcome complacency has been to create a false sense of urgency. It is driven by pressures to perform that actually create fear, anxiety, and anger.”

Herb Stevenson

In the traditional ways of working together, if I need you to do something, I’ll get your commitment to do it, and then I can forget about it. And it’s the forgetting that seems particularly appealing. Out of sight, out of mind. Ignorance is bliss and all that.

And on the other side of it, when we’re asked to do something for someone else, we generally like to make a commitment or agreement to do it. Putting ourselves into a time-box feels good because it gives us a sense of orientation and clarity. We don’t have to consider all of the complex things that may enter our world from moment-to-moment because now we know what we’re supposed to do (i.e. the things we’ve committed to).

It’s the same reason why David Allen, author of Getting Things Done, says we secretly love emergencies; they are tremendously clarifying. We don’t have to wrestle with all of the complexity of our ever-changing reality, and all the things that our super-ego constantly harasses us about. No. The focus is clear. This thing. I need to do this thing. Knowing this, usually unconsciously, we readily sign-up.

When I ask you when you’ll get something done, we’re both incentivized to interpret that data as a commitment. If you accept it, I get the feeling of security. You get the feeling of clarity. And the relationship itself seems to get stronger because, as commitments are made and satisfied, we trust each other more and more.

Of course, at some point, the time-box may not feel so good. New and unexpected things entered your world that needed your attention. Now you’re feeling stressed. Of course, in a way, this is the process working as designed. You wanted to leverage your own feelings of stress or guilt to motivate you, and imagining that your relationship is at stake (or your perceived competence or trustworthiness) ensures you keep yourself on task.

But at what cost? Like burning dirty fuel, it might get the job done, but it leaves a nasty residue. Since we’ll inevitably fail to manage all the fake deadlines we’ve committed to, we eventually disappoint people we care about. And they disappoint us. And worse, we learn the wrong lesson. We tend to take those failures personally, and either make an empty promise to be more reliable next time; or, if someone else violated our agreement, enact vengeance upon them (either openly or passive-aggressively).

But what if this isn’t actually a character problem at all? What if the issue is the unconscious and unexamined assumptions about how work gets done that make us vulnerable to these counter-productive incentives? What if we could get the same (or better) results from taking a different approach? Well, that’s exactly what Holacracy’s approach to projections offers.

5. Projections highlight that we don’t actually want time-management; we want attention-management.

“Directing attention to where it needs to go is the primal task of leadership.”

Daniel Goleman

Projections are the constitution’s only defined construct that deals explicitly with time. If you’re coming from a traditional work environment, then it may seem strange that something as important as time only shows up in this tiny little rule.

The reason for this is because the rules are based upon a different understanding of what it takes to get things done. The conventional paradigm used to frame personal productivity has always been time-management. How should you spend your time? How are your business partners spending their time? But is it really time we care about?

You can easily sit at a desk for many hours and accomplish nothing of value, and you can come up with a brilliant solution to a complex problem in the blink of an eye.

When we use the word time as in time-management we are using the word as a proxy for words like focus, engagement, awareness, consciousness, or attention. Of course, time is easier to measure. Focus or consciousness not so much. So it has its uses, we just shouldn’t forget that it’s not actually, literally time that we care about.

This also explains why Holacracy-style accountabilities are actually just allocations of attention (see Understanding Accountabilities) and why the Lead Link accountability for “Allocating resources” doesn’t mean allocating people’s time.

More than that, the reframing from time to attention should also give us more insight into how Holacracy’s rules have transcended the need for the command-and-control approach of the traditional management hierarchy without losing the actual levers needed to get alignment amongst a group of people.

Holacracy doesn’t allow a single individual to direct others’ time. But it does give everyone the power to direct the attention of others. We can request projects. We can get regular updates on specific checklist items and metrics. We can get transparency into each others’ next-actions, reasoning, interpretations, and tensions whenever we need. And the effect of everyone agreeing to play by those rules is that Holacracy allows the organization to make the best possible use of the consciousness we bring to it.

6. Projections allow us to keep the tensions with the roles that sense them.

“I used to say, ‘If you will take care of me, I will take care of you.’ Now I say, ‘I will take care of me FOR you, if you will take care of you FOR me.’”

Jim Rohn

Have you ever tried to trick someone into raising your child? You know, cleverly slide your little bundle of joy into their house when they aren’t looking? No? Well, cowbirds and cuckoo birds do it all the time. In fact, about 1% of all bird species trick other birds into raising their young for them. It’s an effective strategy. Nasty, but effective.

Sadly, it’s exactly the same strategy we use–again completely unconsciously– when we use anger, guilt, and shame to trick someone else into processing our tension for us. Like the cuckoo bird, we’re trying to trick people into raising our child for us. (A similar nasty unconscious strategy I call Our Inner Gangster exists with unsolicited help).

The main reason Holacracy’s rules say a projection can only be a rough estimate, and is not a binding commitment in any way, is because we don’t want to separate children (i.e. tensions) from their parents (i.e. the roles that sense them). And, of course, we’d never do that consciously. The problem is embedded in some of our old, unexamined assumptions about relationships.

Tensions are tricky, especially in relationships. It’s not always clear that a tension belongs to ONLY one person OR the other. It may seem like a denial of what makes a relationship a relationship. But while you can feel similar tensions, it’s important to remember you can’t feel someone else’s tension for them. (If you haven’t already read Understanding Tensions, I recommend it for understanding this specific point.)

Of course, this doesn’t mean relationships are exclusively about maintaining distinct individual boundaries. That wouldn’t be much of a relationship. It just means that they aren’t exclusively about boundary-less unity either. That principle is captured nicely in maxims like, “Put your own oxygen mask on first,” and “Good fences make good neighbors.” Both autonomy and alignment are important.

With that said, stewarding one’s tensions in the midst of a relationship takes skill. We’re social creatures and having a brain filled with mirror neurons means that I feel sad when I see you feel sad. Emotional alignment is fairly natural. We have to work at autonomy. We actually have to work at managing a healthy boundary, and the intent of the constitutional definition of projections is just a practice to help us do so.

Note: An “I” can feel a “we” tension (i.e. a tension about the relationship itself, not just about the other person), but it will still be just that distinct “I’s” version of it.

One of the reasons why a Holacracy-style projection can never be a binding commitment (by constitutional definition), is to ensure everyone takes responsibility for the outcomes they care about; even if they aren’t the one doing it.

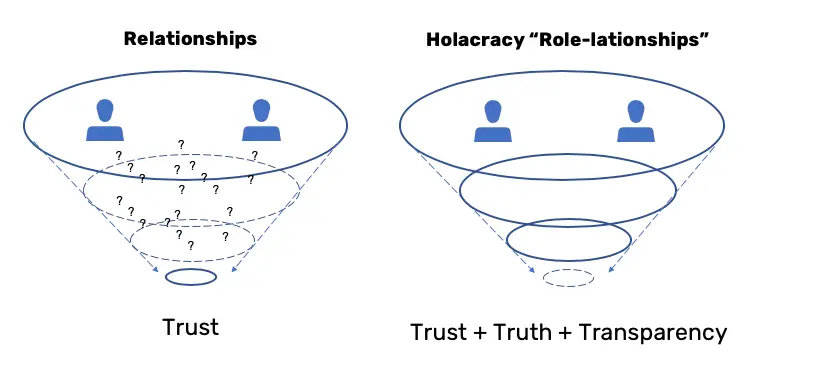

7. Projections allow us to redefine what it means to trust someone.

“Trust is on the rise because transparency is on the rise.”

Gary Vaynerchuk

The rules say you have “No duty to track the projection, manage your work to achieve it, or follow up with the recipient if something changes.” And if this is the new rule, then it’s fair to ask, what was the old one?

Well, normally, our relationships are governed by two implicit rules:

- If I tell you I’m going to do something, I’ll do it (and therefore I am trustworthy).

- If you have to ask me when I’ll do it, that means you don’t trust me.

Now, you may not agree with the specific phrasing, but I think that’s probably pretty close to how most of us learned to think about commitments. Since they care about us and we care about the specific outcome, it seems reasonable to expect that they should care about the outcome too.

But notice something feels off about these rules. Once we stop and look at them, they seem kinda weird. I think that’s because they aren’t really about getting to the truth. They aren’t based on transparency. They’re just rules about managing our reputation, not building a relationship.

This is strange because the old way of doing it puts a high value on trust, which makes sense because within most relationships we don’t have a convenient way to distinguish a commitment to a specific outcome from a commitment to the relationship itself (see point #1).

This is often why the word trust comes up if there are conflicts within a relationship. Again, the boundaries of a relationship are essentially equal to the agreements, promises, or commitments made by the parties who enter them. And you’re not going to agree to a relationship with someone you don’t trust. (Or if you do, the details of your arrangement will account for your lack of trust.)

But trust isn’t the only principle necessary for a healthy relationship. If I can’t ask you for an update on your project (i.e. get transparency into the truth) without it being interpreted as a challenge to you, well, what does that say about the relationship? What does trust really mean?

The constitutional rule states you “must” provide a projection because while we can’t require that people be trust-worthy, we can require them to be transparent. Of course, transparency itself won’t necessarily lead to trust. It just gives you a better barometer to figure out how much you should trust someone. (e.g. If someone’s projections are constantly way off, then you’ll understandably be skeptical the next time they give you one.)

Conclusion

Understanding projections requires deeply understanding big abstract things, like the differences between a relationship-commitment vs. outcome-commitment, importance vs. urgency, time vs. attention, and trust vs. transparency. For most people, these aren’t intuitive distinctions. So, it’s understandable why Holacracy’s 4.1.1(c) rule about projections seems weird.

But the practice is important. Maybe counter-intuitive. Maybe awkward. But important. If someone asks, “Can you send me that report by next week?” be prepared to give a nuanced answer, like, “Well, I think so…that’s my projection. But remember, that’s not a commitment…although, feel free to contact me any time for an update.”

And, I get it. Statements like that are awkward. But if you want to genuinely trust each other, live unburdened by the specter of blame and guilt that haunts most relationships, and also actually get stuff done, then I invite you to experiment with Holacracy’s way of dealing with timeframe commitments.

The rule on projections may seem crazy. And it may make for some awkward and nuanced conversations at first. But given what we have to gain by using it as a shared distinction of how to handle deadlines and commitments that doesn’t depend on creating fake deadlines for each other, I think it’s even crazier not to try.

Holacracy Basics: Understanding Deadlines and Projections (Part 2)

Holacracy Basics: Understanding Deadlines and Projections (Part 3)

Join me on the Holacracy Community of Practice.

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner’s Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-learning suite → Self-Management Accelerator