Introduced in Holacracy Constitution v5, rules about “relational agreements” were added as a complement to governance. This made some things more clear, but also introduced some complexity.

But before I say too much about them, I need to introduce a presupposition that I’ll also emphasize several times through the article; if you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Just like with governance, if things are working well as they are, leave them alone. Relational agreements should be tension-driven. Now, let’s get into the details.

Three Distinct Types

Practically speaking, relational agreements aren’t just a specialized tool for a specialized job, they are actually three different specialized tools for three different specialized jobs:

- Agreements between two or more people for the purpose of helping partners resolve interpersonal tensions. Example: “When Reynold is complaining to Martha about a work or partnership issue, Martha agrees to ask non-reactive clarifying questions about the intent (e.g. “Are you looking for advice or do you just need some space to vent?”).”

- Agreements between the organization and one or more people for the purpose of clarifying expected behavior of the person/s not any of the roles they fill. Example: “When planning to take time off from work and I can reasonably expect that others may be impacted by my absence, then I agree to notify all relevant partners in advance.”

- Agreements required by the organization for the purpose of defining terms of employment or partnership. Example: “I will not make any verbal, written, or physical contact with another partner that denigrates or shows hostility toward them because of his or her race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or national origin.”

I’ve found that these differences make it extremely challenging to speak coherently about all three types simultaneously. Several points of emphasis I want to make about the first two types, are, practically-speaking, untrue of the third. Therefore, this article will focus on the first two types, and I’ll publish another article specifically about relational agreements and employment contracts.

Here is a summary of what you need to know:

- Although not technical-sounding, “relational agreement” has a specific definition in the Holacracy constitution.

- Generally speaking, relational agreements are about the people, not the roles.

- Relational agreements must be focused on shaping concrete behaviors, not requiring someone to adhere to an abstract principle.

- Relational agreements can only be requested, not demanded.

- In the absence of guidance about HOW to explore, request, or renegotiate a relational agreement, there are two meta-agreements which can be particularly helpful.

In addition to the above points, I’ve added a bonus section:

6. Frequently Asked Questions:

- What makes a good relational agreement versus a bad one?

- How do you request one from somebody?

- How do you make sure someone follows a relational agreement they’ve made?

“Relational agreements” have a specific definition

Although not technical-sounding, the term “relational agreement” has a specific definition in the Holacracy Constitution.

Article 2 of the Holacracy Constitution v5.0 details the “Rules of Cooperation” for partners in the organization, which includes the section on what relational agreements are and how they are supposed to work. Let’s start with what the constitution actually says:

As a Partner, you may have “Relational Agreements” with other Partners. These are agreements about how you will relate together while working in the Organization, or about how you will fulfill your general functions as Partners of the Organization. They may add to or clarify the duties in this Article, but they may not conflict with them.

Relational Agreements must remain focused on shaping behaviors that generally underpin work; they may not set expectations of work to do in a Role, nor expectations about how a Partner will prioritize across different Roles. Further, they may only specify concrete acts to do or behavioral constraints to honor; they may not include promises to achieve specific outcomes or embody abstract qualities.

As a Partner, you may request a Relational Agreement of another Partner for your own personal preferences or to serve a Role you fill. That Partner may accept or reject the requested Relational Agreement based on their own personal preferences. Unless otherwise agreed, either party may later terminate the Relational Agreement by notifying the other party.

As a Partner, you have a duty to align your behavior with any written Relational Agreements you have made. Anyone facilitating a meeting or process for the Organization may also enforce these Relational Agreements during that meeting or process, as long as they don’t conflict with anything defined in this Constitution.

There is a lot to unpack, so let’s look at each of the important elements one-at-a-time. But to give you some clarity as we begin, here are some real examples of what a Holacracy-style relational agreement looks like:

- A training cohort agrees to automatically honor any requests for confidentiality.

- Members of the circle agree to refrain from sustained use of their cell phone during scheduled meetings.

- Upon request, Tommy agrees to speak inarguably; i.e. to ‘own his experience’ (e.g. “I think…” “It seems…”).

Now, two quick notes about these examples. First, I’m not necessarily saying these are good relational agreements — just that they meet the Holacracy definition.

Second, these real examples were created to provide clarity within actual relationships to resolve actual tensions. I’m only sharing them to convey the proper energy and focus of a relational agreement, and not to suggest that these specific agreements are somehow objectively or universally helpful. If you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Focused on people, not roles

Generally speaking, relational agreements are about the people, not the roles.

The governance records of your organization directly capture the expectations, authorities, and restrictions that apply to the work of the organization. So, an accountability like “Updating the company’s website” for a Webmaster role defines an expected activity, but it doesn’t say anything about the role-filler’s personal behavior.

So, what do you do if the Webmaster role-filler doesn’t respond to your text messages? Or, what if Kevin is always late to meetings? It’s not just about a single role he is filling; it’s a personal behavior that impacts all of his roles.

Governance isn’t a good tool for resolving these tensions, and this is where pursuing a relational agreement may help. While relational agreements can’t be used to set prioritizations or make promises to achieve certain outcomes, they can be used to help people resolve interpersonal conflicts by exploring and defining concrete behaviors to improve our working relationships.

And if you’re thinking, “Well, why not just go talk to them about it directly?” then you’re on the right path: Talking with people directly about their behavior is often the best option, even though Holacracy’s rules say nothing about how to make that conversation happen (though I’ll share some best practices in the FAQ).

In addition, if you’ve tried the direct feedback approach you may know how easily these conversations can blow up in your face. This is where a relational agreement (or the pursuit of one) might help.

Focused on concrete behaviors, not principles

Relational agreements must be focused on shaping concrete behaviors, not requiring someone to adhere to an abstract principle.

This topic deserves its own article, because there is a principle here which is generally applicable to all of Holacracy practice: the distinction between principles (abstract qualities) and practices (concrete behaviors).

And it’s a distinction we usually don’t need to make. Parents instruct their children to “be nice.” A romantic partner may request “feeling loved” by the other person. But as natural as these might be to say, they are usually not very helpful to hear.

The problem with asking someone to adhere to a principle like “be nice” is that it doesn’t give the kind of clarity someone needs to reasonably fulfill their agreement. How would you know someone was nice? What observable behavior would tell you one way or another?

Principles work well as heuristics to help an individual subjectively interpret and apply. But if I want someone else to agree to something, and I want them to help me meet my need, the more concretely it is described, the better.

Of course, just like governance, there is no such thing as perfect clarity or perfect concreteness. It’s a spectrum; use what makes sense to you. But just to drive the point home, here are some real-life examples to help illustrate the difference and give you a sense of why defining a concrete behavior often works better:

- Imagine you’re freaking out about something and someone close to you tells you to “calm down.” Now, imagine the same scenario, but instead the person tells you to “take a deep breath.”

- If two children are fighting over a toy, rather than telling them to “share,” tell them instead to “take turns.”

Of course, defining a satisfactory concrete behavior usually isn’t easy. But that’s the point. Doing the hard work of clarifying now, improves your chances of making things better going forward. And again, remember: if you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

Relational agreements should only be voluntary

Relational agreements can only be requested, not demanded.

Relational agreements should only be voluntary. And much like the previous point about abstract principles vs. concrete behaviors, there is a spectrum of requests vs. demands, but one on which we can make some meaningful and non-obvious distinctions.

Note: And if you’re wondering how agreements “required” by the organization can still be considered requested not demanded, follow me on Medium so you won’t miss the next post.

The best definition I found for the difference comes from Marshall Rosenberg, pioneer of Nonviolent Communication who says, essentially, if you feel upset when someone turns down your request, then it wasn’t actually a request; it was a subtle demand.

This is a big deal, because one of the reasons relational agreements were added to the Constitution was to reinforce the principle that people are only responsible for what they have consciously agreed to.

So, what do you do if someone is annoying you ? Imagine that they make a mess of the microwave in the break room and never clean it up, or that they talk too loudly on the phone. Do you just request that they stop? Well, yes.

But of course, how you ask matters. And most of us don’t intuitively make requests in ways that make it easy for others to help us.

Using relational agreements in practice

In the absence of guidance about HOW to explore, request, or renegotiate a relational agreement, there are two meta-agreements which can be particularly helpful.

In a way, we’ve come to the end of what the Holacracy Constitution tells us about relational agreements. It defines them, but that’s about it. In other words, it doesn’t say much about how these agreements should be enacted.

Meaning, some of the most interesting questions around the process of requesting or updating agreements are left unspecified.

In the absence of rules about the process-side of relational agreements, I’ll do my best to try and answer specific process questions in the FAQ. But first, I want to share two meta-agreements (i.e. they are themselves just relational agreements), which I think provide a simple and effective-enough foundation. They are:

- I agree to bring it to someone’s attention when I think they may have violated a relational agreement they have made.

- If brought to my attention, I agree to explore whether or not I may have violated a relational agreement I have made; and if I have, upon request, to explore any impact on others before I realign my behavior or change the agreement.

Now, I could say a lot about the reasoning behind these agreements, but hopefully it’s self-evident. I feel confident in saying that from my experience, these more-or-less capture the implicit expectations around how relational agreements get enacted in healthy environments.

With that said, these agreements are just that. They don’t really provide any meaty details, and the details around this stuff are really important. For those who are interested, the following section will hopefully provide some additional clarity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Note: I’ll do my best to try and answer some common questions, but first I want to clear that we’re moving beyond explicit constitutional rules here and into some personal recommendations. And of course please refer to specific methodologies like Nonviolent Communication, Systems-Centered Therapy, or MetaRelating for more expert details.

A) What makes a good relational agreement versus a bad one?

I’ve come across a few criteria, but remember: anything that moves things forward is good.

- It’s tension-driven. If you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one. Some people are understandably put off when they first here the term “relational agreements,” because it conjures up an impression of someone trying to squeeze all of the juice and heart out of a relationship. And I’m sure someone could try to use them that way, but the opposite is true. A good relational agreement is directly connected to a real tension felt by someone (i.e. they feel discomfort/pain). Meaning, they shouldn’t be artificially pursued to prevent discomfort, but should be used to help process some of the natural discomfort that arises in any relationship.

- If possible, they should be stated in the positive. In other words, it’s usually better to request someone do something rather than request that they stop doing something. For example, imagine a husband requests that his wife spend less time at work in the evenings. She agrees, and starts spending more time out with her friends. That’s not the outcome he wanted. So, rather than request people agree to, “I won’t leave trash in meeting rooms,” instead ask them to agree to something like, “I agree to clean up after myself.” Note: Relational agreements required by the organization are often stated in the negative; i.e. anti-harassment, anti-discrimination, anti-retaliation, etc.

- It’s actually an agreement you want (i.e. you don’t want something else). When we feel tension with someone there are lots of meaningful types of conversations to have to resolve that tension. For example, 1) maybe you just want to be heard and understood, 2) maybe you just want to offer some feedback for the other person to consider, or 3) maybe you want to clear the air with someone. None of these necessarily include a request for a relational agreement. And really, a relational agreement isn’t a type of conversation at all, but a possible outcome of any relational conversation.

- They can be one-time or ongoing. Even though the rule in the Constitution stipulates that you must align your behavior with any “written” relational agreements, it’s helpful to consider non-written or one-time agreements as well. For example, if you’re ever concerned about being understood in a conversation, you can request this one-time agreement: “I’d like to share something. It’s important to me that you get what I’m saying, so after I share, would you agree to say back to me what you heard me say and let me correct or clarify anything you missed?”

- They should be as specific as necessary. There is no such thing as perfect clarity. And especially when it comes to agreements between people, we needn’t make them any more or less detailed than is required to resolve the issue. How do you know it resolves the issue? Simple: If the speaker feels like their tension has been resolved — that makes it good enough for now. Try it, and update it as needed. Again (and I promise this is the last time I’ll say this…) remember: if you don’t need an explicit agreement with someone, don’t artificially pursue one.

B) How do you request one from somebody?

- Do your own pre-work. Typically, you’ll need do some pre-work to ensure that you’re coming to the other party/parties with the right energy (i.e. the energy of a requester not a demander). This form of inquiry often reveals other options and pathways as well. You may discover that it’s really not a relational agreement you need, but a change to governance. Or you might need to brainstorm, “What concrete thing could they do to make me feel better?” If you’re coming to the person with openness and curiosity, you may be able to explore options together, but getting some clarity for yourself often helps.

- Treat it like a conversation, not a presentation. Coming up with a concrete request is great, but don’t expect it to go well if you simply drop it unexpectedly in someone’s lap. Get consent first before you jump into the details (e.g. “Do you have time to explore a relational thing with me?”). In addition, expect the listener to have questions about what you’re sharing, and treat their need to understand your request as equal to your own need to be understood.

- Remember that just pursuing a relational agreement may be enough. After talking for a bit, you might discover there isn’t anything you want to request. Your tension is resolved. Now, I would generally advise to keep looking for a request a little longer in this scenario, but it also may be the case that you simply needed some space to share. If this happens, I’ve found that there is usually still a request I can make for the listener to simply, “consider” what I shared going forward, but no need for any agreement.

- Write it down. I know, I know—seems needlessly formal, right!? Well, maybe it is. But I can tell you this: you’re potentially wasting the value of the clarity you’ve created if you don’t capture what has been agreed to. Having an explicitly-written agreement captures the specifics, which are what allow you to move forward. Again, it might not always be needed, but better safe than sorry.

C) How do you make sure someone follows a relational agreement they’ve made?

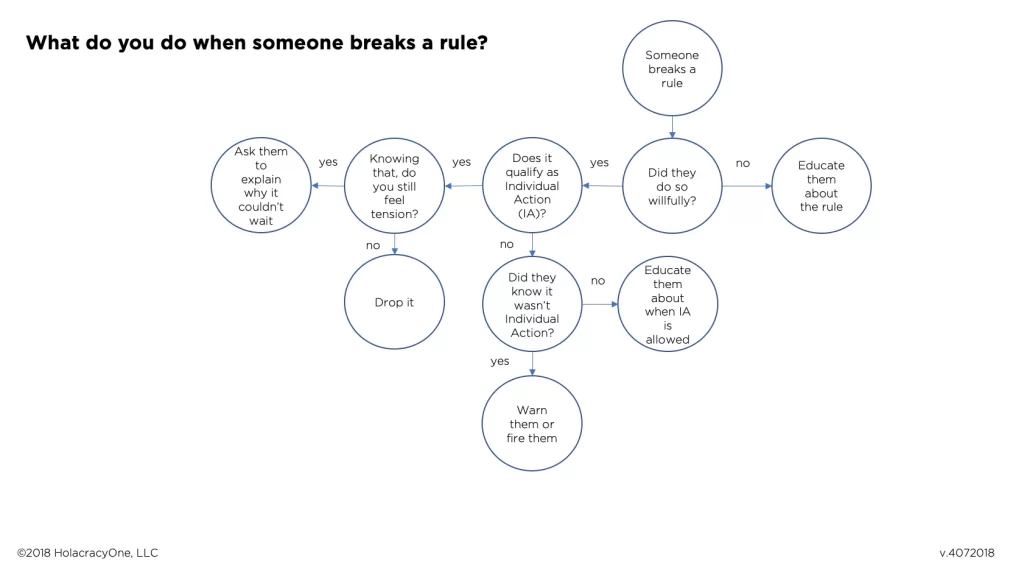

- A relational agreement isn’t a promise; it’s only an intention to adhere. I’ve spoken about this principle generally as the Intention to Adhere, which is trying to describe the concept that there are different types of rules, and literally, sometimes rules are made to be broken. So, what do you actually do if someone fails to adhere to an agreement that they made? Well, you just bring it up, “Hey, I remembered that you made this agreement and I think you might have broken it; would you be willing to explore that with me?” As I mentioned in #5, it may help to have some sort of meta-agreement about how to process potential violations. Additionally, you can refer to the diagram below which applies equally to governance (and any agreement, really).

- They can be aspirational, but should remain realistic. Relational agreements function like hyper-charged reminders in that they help reinforce new behavior. If you’re requesting that someone change a habit, expect that at some point they’ll fail to meet it. But equally, if you’re considering an agreement someone else is requesting of you, don’t agree unless you can realistically imagine yourself doing it. Some people will try to escape an awkward conversation by simply agreeing to whatever they’re asked. Don’t do that. Take the request seriously and ask yourself, “Knowing what I know now, is this new behavior something I can reasonably expect of myself?” If not, tell them and keep exploring.

Conclusion

Relational agreements aren’t just a specialized tool for a specialized job; they are actually three different specialized tools for three different specialized jobs.

And I haven’t been able to cover them in nearly the amount of detail they deserve, especially when it comes to required agreements, so make sure you follow me on Medium to get the latest articles.

Again, some people get the impression that relational agreements are intended to legislate away all of the real feeling and juice and heart out of a relationship, but that’s not true.

Like governance, relational agreements are a form of liberating structure, meaning they impose order on something not to restrict it, but to allow it to more fully flourish. Just as lines on a highway allow everyone to get to where they want to go faster and more safely, just think of relational agreements as a way for us to meaningfully make each other’s lives more wonderful.

Join me on the Holacracy Community of Practice.

Read “Introducing the Holacracy Practitioner Guide” to find more articles.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-learning suite → Self-Management Accelerator