During my work helping clients roll out Holacracy in their companies, I’ve noticed that in the first few months, they naturally try to use Holacracy’s structure to reproduce the structure they’re familiar with. But Holacracy isn’t designed for this old structure, so it feels like they’re trying to fit a square peg in a round hole.

On the surface, Holacracy is just a set of rules. But learning the rules is just the first step in adopting the new system. Beyond the surface, Holacracy incites us to think differently about how authority and accountability flow between roles. This dissonance between old vs. new paradigm is rather obvious during governance meetings, when a team member proposes adding an accountability to a role.

My goal with this article is to give you some tips on how to write roles’ accountabilities by avoiding common pitfalls, so that the work expected from a role is 1) clear, 2) aligned with Holacracy’s distributed authority, and 3) achieves what you’re trying to do.

Here is a list of verbs often used in accountabilities in order to mimic a conventional relationship between roles. I explain why they aren’t the best choice, then give you alternatives.

Quick recap: an accountability in Holacracy is an expectation placed on a role for doing something. They usually begin with an -ing verb to convey that it’s an ongoing activity (and not a one-time project or action).

Accountabilities starting with “Enforcing…” or “Ensuring…”

Usually indicates an attempt to mandate a result, e.g. “Ensuring 20% growth in revenue”. It’s typical “what by when” thinking: setting a target and pushing toward it. However, we cannot mandate reality to be a certain way, we can only influence it as best as possible. The “how” to achieve that goal is the activity we want to capture as an accountability. For example, instead of “Ensuring 20% growth”, one could propose “Generating demand for our products and closing deals”. Then, it’s up to the circle to prioritize this sales activity versus other work in order to increase the odds of achieving the 20% growth target. (Prioritization of the work happens outside of governance; it’s set by the Lead Link by default).

Sometimes, these accountabilities convey an intent for the role to control the work of other roles, e.g., A Customer Service Lead with an accountability for “Ensuring that all Customer Service Agents provide a service of quality to customers”. The problem here is that this accountability is not achieving the intended goal: an accountability does *NOT* give any extra authority to control how another role does its work.

To accomplish the intended effect, an alternative would be to propose adding an accountability on the Customer Service Agent role itself for “Responding to customers’ questions and helping them get what they need from our company, while offering the customer a positive experience of going through that process”. Then it’s up to the Lead Link of the circle to assess whether each person in that role is a good fit for the role — and to remove them from the role if they’re not.

Another alternative would be to create an additional role, e.g., Customer Service Experience, accountable for “Implementing tools and processes to help Customer Service Agents support our customers as effectively and pleasantly as possible”, and to add an accountability on the Customer Service Agent role for “Helping customers by following the process defined by Customer Service Experience”.

These are just examples — there are many ways to organize the work and define how roles interact. Some are better than others, but Holacracy isn’t here to tell you which way to choose; it will simply force clarity around it.

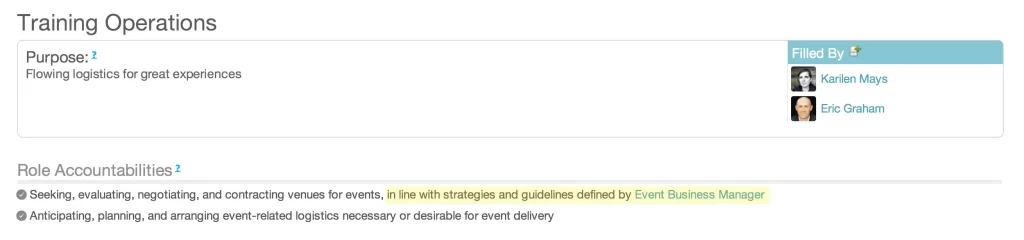

Lastly, I’ve noticed that often times, results that we want “enforced” or “ensured” are clues to the Purpose of a role. Our Training Operations role at HolacracyOne has a Purpose of “Flowing logistics for great experiences” — that’s certainly something he wants to “ensure” happens!

Accountabilities starting with “Collaborating with…”, “Working with…”

Often used to ensure that a role will work with others to do its work. In fact, the role-filler already has the authority to work with whoever they want to get their work done. Spelling it out in an accountability is often due to a misunderstanding of the basic authorities given to a role-filler in Holacracy — i.e., anyone can already collaborate however they want with whoever they want to express the purpose or accountabilities of their roles. As a result, those verbs may have the counter-productive effect of implying that if it’s not spelled out, then a role-filler must do its work without collaborating with others (which is not the case!).

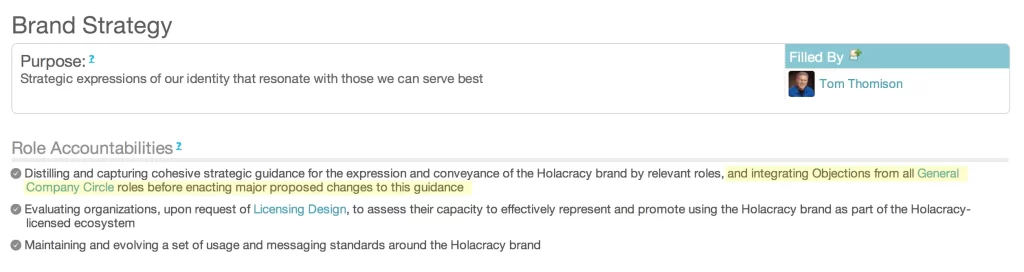

If we really want a role to “collaborate” with another role, then it’s much clearer to specify the nature of that collaboration. Do we want the role to “consider suggestions” from another role? Or “integrate objections”? Or even “integrate input”? Or do we really mean “Execute … as directed” by another role? Some options are better than others depending on the context, but regardless of which one we choose, Holacracy pushes us to make a conscious decision about it.

Accountabilities starting with “Overseeing…”, “Supervising…”, “Managing…”

Usually indicates an attempt to control someone else’s work. As explained above, an accountability does NOT convey this authority. Again, Holacracy forces us to be clearer on the relationship between roles. Ask yourself the question: what type of activity are you envisioning when “supervising” the work of another role? Is your goal to support and coach them because you have more subject matter expertise? Or do you want your role to be a gatekeeper, so that projects can’t be completed without your approval? Or something else? Here is how you can improve the proposal depending on the actual need/tension behind it.

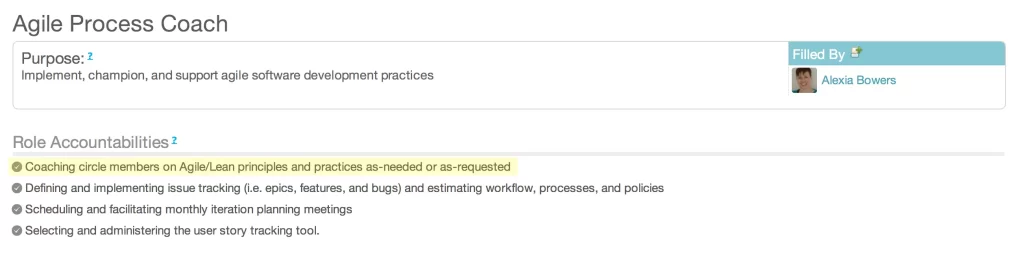

- If you want to offer support to other roles, you can simply call it out by using one of those verbs instead: “Supporting…”, “Assisting…”, “Coaching…”.

- If you want your role to be a gatekeeper to another role’s work, call it out clearly. More about how to achieve that in the next section.

One caveat about “Managing”: even though using “Managing” is sometimes an attempt to control another role’s work (e.g., “Managing the Customer Service Agents”), at other times it’s a perfectly appropriate accountability when it’s describing the administration of something (e.g., “Managing relevant vendor relationships with Internet providers”).

Accountabilities starting with “Approving…”

Usually indicates an attempt to create a gatekeeper over some process or resource. Here again, an accountability does NOT limit other roles in any way, so the desired result is not achieved with such an accountability. If you think about it, technically an accountability for “approving” means that other roles can expect this role will be “approving” stuff. But it doesn’t constrain any other roles to align with this decision…

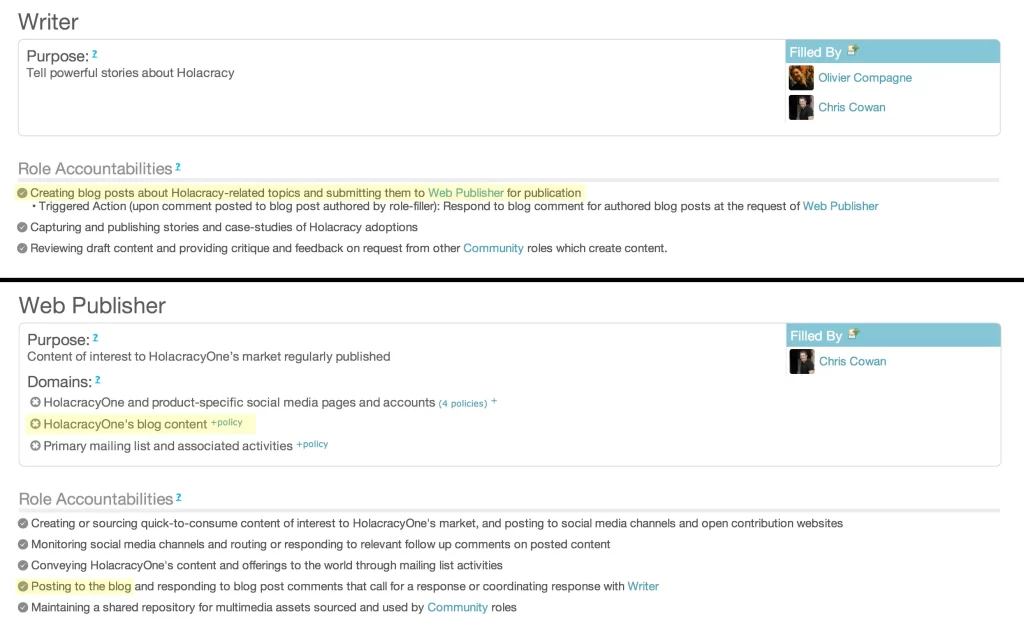

Instead, you usually want a Domain or a Policy to restrict other roles from impacting a particular process or resource. For example, at HolacracyOne I currently fill the Writer role accountable for writing blog posts. There’s also a Web Publisher role acting as a gatekeeper to our blog content. To get this blog post published, I’ve had to write it and submit it to Chris, in his Web Publisher role, who has the authority to decide whether to publish it or not (thanks Chris for approving it!). His role has exclusive control of our blog because of the Domain it has over “HolacracyOne’s blog content”. It means no other role can impact the blog content without his permission.

Another way of making sure other roles can’t proceed without your approval is through a policy. Here is an example of policy at HolacracyOne that limits how other roles can bill clients: they can only use billing models approved by our Finance role.

Just Rules of Thumb

I hope you find these tips useful when crafting your governance proposals. Take them as rules of thumb based on what I’ve seen in practice, not hard rules about which words to use or not to use. You could probably find exceptions with each of them.

Hopefully, these tips also help you see that the various elements of governance (circle policies, roles’ accountabilities, purpose, and domains) each have their specific use. They are a palette at your disposition to achieve the structure you’re looking for. In the early stages of a Holacracy implementation, it’s common for people to focus on accountabilities and forget the rest — perhaps because accountabilities are the most intuitive of the four elements. When you’re comfortable enough, try to make use of the entire palette and you’ll be able to achieve much clearer and more powerful governance outputs.

To learn more about self-management, join a community of pioneers and check out our e-learning suite → Self-Management Accelerator